Behaviour

Our first module is the most fundamental: behaviour. The aim of systems neuroscience is to figure out the biological basis of thought and behaviour. This is done by correlating biology -- notably, measuring or manipulating neural firing rates -- with behaviour. That's how it is done even if we are more interested internal reasoning, emotion, or motivation than in behaviour itself: since we cannot yet directly measure thoughts, the human subject or experimental animal's actions are always used as a proxy. For a cognitive feature of interest, choosing the right behaviour to train or measure is no simple task. To yield insightful experiments, the behaviour must be the right combination of robust, naturalistic, and truly reflective of the relevant thought process. In this module, we wanted to find out to what degree rats are capable of recognizing and manipulating objects. We know that rats excel in a foraging task, in which they learn to navigate to a moving spot of light in order to earn a sugary reward. This indicates that they are capable of locating and navigating to sensory 'objects'. This, however, is a very limited component of the kinds of interactions humans have with objects, which culminates in the use and invention of complex tools. Taking one step toward this extreme, we would like to know whether rats can learn not just to navigate to an object but also to move it to a target location. Specifically, we attempted to train our rats to push a marble into a hole. Note that this is more complex than, say, pushing a lever to earn a reward; pushing a lever simply requires a particular motor act when the rat is in front of the lever. Getting a marble into a hole, however, requires a distinct set of pushes depending on the location of the marble and hole. This is a more flexible type of behaviour; it requires an abstract understanding that the marble should fall in the hole and that the rat is capable of causing that to happen. Can rats easily learn this kind of object-oriented thinking? Can we design a behavioural assay to effectively test that question? If yes to both, can we look in the brain and discover the neurobiology behind this simple model of object recognition and manipulation? With this tricky task, nuanced question, two rats and one week of training, we were doomed to inconclusivity. Nonetheless, here are our methods, data, and conclusions:

Materials and methods

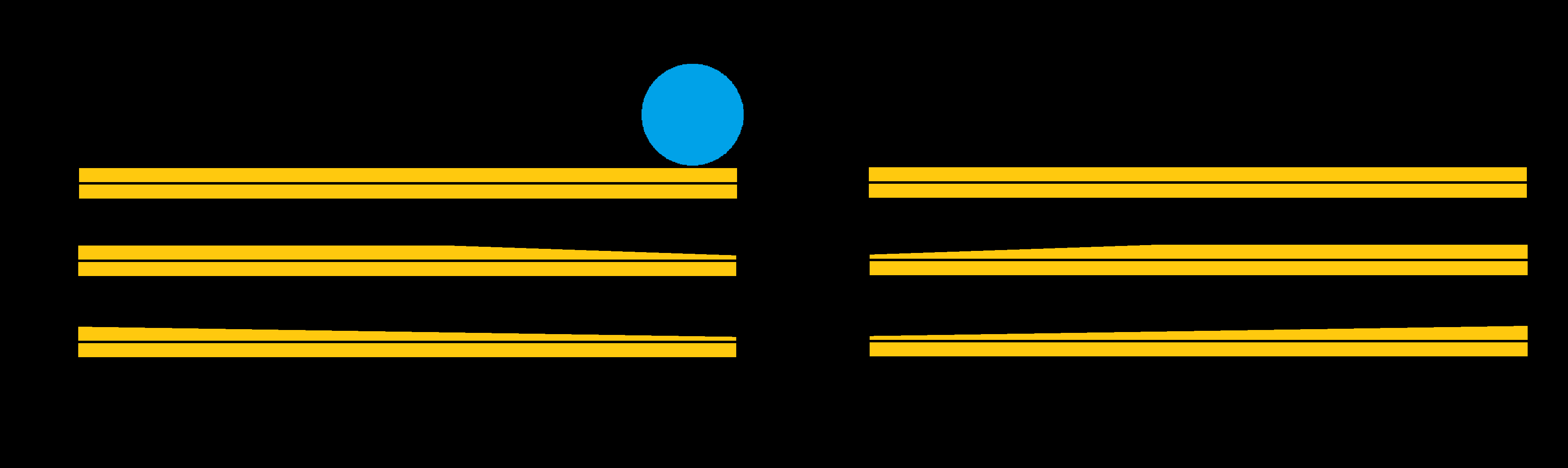

We trained our rat in 13 sessions of 30-50 minutes over 9 days, in a 46 x 80 cm behaviour rig. The floor consists of two stacked rectangular acrylic boards: one with a 3-cm hole in the center to fit the 2.6-cm marble, and the other with larger central hole of 20-cm diameter. Stacking these allowed us to place three different 3D-printed circular sections in the middle (schematic below). One was otherwise flat (most difficult); one was sloped so that the marble would slide into the hole if it came within 10 cm of the center (medium-difficulty); and one was sloped across the entire 20-cm diameter (least difficult). To make it easier for the marble to roll into instead of past the hole, we sanded the board to add friction, and installed grooves along diameter-sections of the most-sloped centerpiece.The reward port contained an infrared beam and detector and a strawberry-Ribena juice dispenser. If the rat sticks its head into the reward area at an appropriate moment, the IR beam breaks and then a drop of juice is dispensed. The marble detector similarly contained an IR beam that, when broken by a marble falling through the hole, would send a signal to the computer. Each sessions was filmed with an overhead IR camera. We coded all training automation and time-stamp-saving in Bonsai. Video analysis was performed in MATLAB. Behavioural training progressed through several stages. First, the rat habituated to the behaviour rig and human handling over 2 days. Next, over 6 days the rat was trained on an association between a beeping sound (on for 50 seconds or until the rat arrived at the reward port, and then off for 10-30 seconds; as training progressed the beeping was reduced to 20 seconds on) and a juice reward in the reward port. During this training, when the rat pokes its head in the reward port, it will receive juice, if and only if the beeping sound is on at that moment. After entraining this beep-juice association, we put the marbles in the arena. The arena was now set up with 5-7 marbles placed around the outer circumference of the centerpiece at the beginning of each session. The plan at this point was as follows: reward any interaction with marbles by turning on the beeping and reward availability; once the rat starts to regularly interact with marbles, decrease this manual rewarding and only provide reward (automatically) when a marble falls through the hole (of the least difficult centerpiece); once the rat starts to regularly push marbles into this sloped centerpiece, switch to the medium-difficulty centerpiece; and once the rat comes to regularly push marbles into the medium-difficulty hole, switch to the flat centerpiece. Finally, once the rat comes to regularly push marbles into the hole, modify the parameters of the task to test whether the rat has truly learned the abstract, object-oriented thinking we attempted to entrain or if it instead learned a simpler rule with which it just happened to successfully get marbles in the hole. For example, we could place marbles in another arena adjoined to the one with the hole by a narrow passage. It is unlikely for the rat to push marbles across the narrow passage unless it truly possessed the goal of getting marbles into the hole. Given just one rat and 3 days of training with marbles, this training protocol did not yield a definitive result. As shown below, we instead were able to make some observations about our rat's particular habits during training. We modified our reward protocol accordingly, now providing chocolate treats by hand whenever the rat interacted with the marble or pushed it into the hole. This more effectively encouraged the rat to interact with the marble.

Results

Days 1-6 (sessions 1 - 8) -- Beep-Juice-Association Training: Over these sessions, the rat was trained on the above-described beep-juice-association training protocol. While managing to stay awake, the rat only sporadically visited the reward port. After some manual intervention -- dropping a trail of juice leading to the reward port -- its interest in the port marginally increased. As this point, we increased the inter-beep-interval (up to 30 sec) and decreased the beeping duration (down to 20 sec). However, a robust beeping-followed-by-running-to-collect-juice association never fully formed.

Days 7 - 9 (sessions 9 - 13) -- Marble-Pushing Training: Sessions 9-11 followed our original training protocol from Materials and Methods. However, during these sessions the rat demonstrated a surprising behavioural pattern that led us to modify our reward protocol in sessions 12-13. At the beginning sessions 9 - 11, and sporadically throughout the session, the rat demonstrated a high intrinsic interest in the marbles. It interacted with them, mostly ignoring the beeping and potential juice reward that followed. Indeed, with the least-difficult centerpiece in place, the rat quickly pushed several marbles into the hole, and then ignored the resulting reward availability at the port (video below). This demonstrated an intrinsic interest in interacting with the marbles, which could potentially be shaped toward specifically pushing them into the hole. It also showed, however, that our beep-juice association was inadequate for entraining this task.In sessions 12-13, we modified our reward protocol accordingly, now providing chocolate treats by (Lory's) hand whenever the rat interacted with the marble or pushed it into the hole. As this required no effort on the rat's part beyond gulping up a chocolate lowered to its mouth, it now collected its reward every time the reward was earned. During session 12, the medium-difficulty centerpiece was in place, and the rat was rewarded each time it pushed a marble even slightly -- however, as the session progressed only pushed toward the center of the arena were rewarded. During this session, the rat pushed 6 out of 7 marbles into the hole. In addition, when it pushed marbles away from the center, it started to demonstrate a new behaviour: stopping and looking upward, perhaps in anticipation of Lory's sugar-bestowing hand (video below). During session 13, the most difficult centerpiece was in place, and the rat was only rewarded for pushing a marble toward the center. It pushed 4 out of 5 marbles into the hole, and demonstrated a sustained interest in the marbles.

Conclusions

We were interested in finding out to what degree rats can learn abstract, object-oriented tasks. The task we selected was to push marbles placed around an arena into a small hole at the center of the arena. Previous work has shown that rats can learn conceptually similar and physically even more difficult tasks, such as basketball (video below). Our goal was to optimize a training protocol for a simpler task; once learned, our marble-pushing task could then be systematically modified and extended in order to probe exactly what types of abstract object-manipulation tasks rats are capable of. We did not get that far after 8 days of training. However, we did make one key update to our original materials and methods -- replacing the 6 days of inefficient juice-beep-association training with a chocolate reward as soon as the rat pushes the marble. With this change, our rat began to learn to push marbles. We believe that some proportion of rats trained on this protocol would learn to push marbles into a hole, and could then present a rodent model system for studying the cognition and neurobiology of object manipulation.