Behaviour

The purpose of our first course in Experimental Neuroscience was to enrich our understanding and perspective of one of the fields most established approaches; behavioural experiments. By observing animal behaviour in response to stimuli and neural manipulation we have opened a window onto how the nervous system controls a range of behaviours from simple reflexes to complex social interactions. In addition to simply observing animal behaviour the work of B.F Skinner amongst others have demonstrated the possibilities of observing trained behaviours. Through simple reinforcement learning animals of all species can be trained to complete more complex tasks in response to a rewarding stimulus. The result provides researches the opportunity to observe animal behaviours in response to tasks that allow us to probe into cognitive functions that can be difficult to observe in a purely ethological setting such as memory and motivation. Over the years our techniques and approaches have become increasingly more sophisticated and animals can be elegantly trained to conduct behaviour unimaginable in the wild. However, as entertaining as behaviour like this can be to watch it raises serious questions regarding whether the animals truly perform the behaviour in the way we assume they do. For example, at a glance it could be interpreted that both rats are engaged in a game of basketball, both competing to beat the other. Yet, what is the rats' understanding of the task? Is it likely that it understands that it is competing against the other? Would it still be able to perform the task well if small changes were made to the rules or the arena? It was these questions we aimed to probe with our first two week project. To initially help gain a perspective of a trained lab animal we split into small groups with one unwitting student taking the role of the trained animal and the others those of the trainers armed with a single clicker. The underlying premise being one utilised extensively in animal training since the pioneering work of Ivan Pavlov; that the click is given in unison with a reward until the sound of the click itself becomes synonymous with the idea of being rewarded. (In our short demonstration, any real rewards were alas unforthcoming).

What was quickly discovered by all students unfortunate enough to be chosen as subjects was that the interpretation of what behaviour was being rewarded could be rife with confusion. Subjects could increasingly find themselves repeating unwanted behaviours that they had incorrectly perceived as the object of the task. In addition those with the training responsibilities quickly discovered the need to developing a training plan so that the subjects didn't become too bewildered when the availability clicks dried up as the trainers attempted to move them onto the next part of the task.

Overview

Armed with our new experience we split into two groups to attempt an animal training task with rats. The initial aim was to design an experimental set-up where a rat would be trained, semi-automatically, to drop marbles into a hole in the floor for a reward. Were we to be successful at this our extended aim was to pursue the question of how aware of the task the rat actually is. To examine this we would open up an extension of the setup to a new room containing marbles to see whether, in pursuit of additional rewards, the rat would move out of it's trained space, acquire a ball in the extension, and return it to the hole for a reward.

Materials

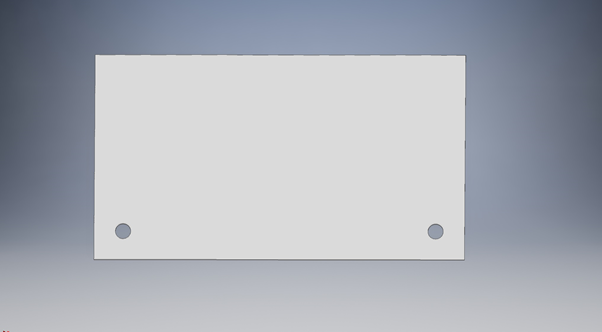

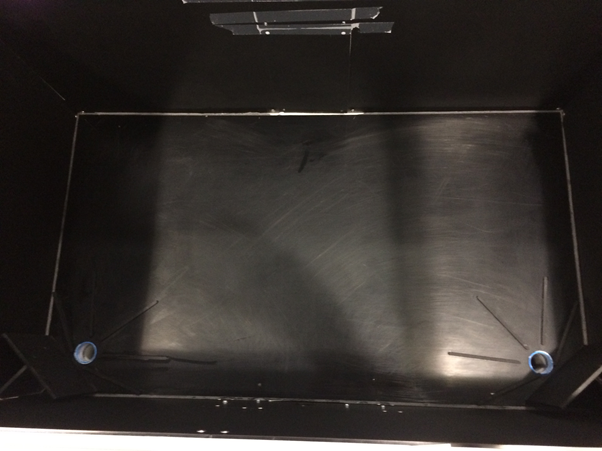

In our group we decided to opt for a relatively simple approach. Using the Autodesk Inventor program we designed and laser cut a black acrylic floor space (46 x 80cm) with two holes in each corner (3cn diameter) and additional acrylic components (5 cm length, 5mm height) stuck to the floor to both act as guides for the marbles (2.6cm) and to block the corners and avoid any rogue marbles being stuck in the angles of the corners. In addition the both the acrylic floor and the marbles were sanded to create additional friction in a "pool table" effect. This was completed after initial observations that the lack of friction made it difficult for the marbles to be static in the arena. It was thought that if the marbles had additional motion aside from those generated by the rat it would weaken the learning process of the rat association movement of the marbles with it's own actions.

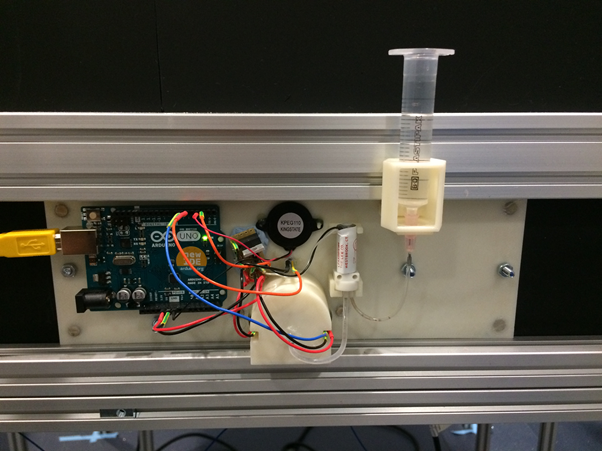

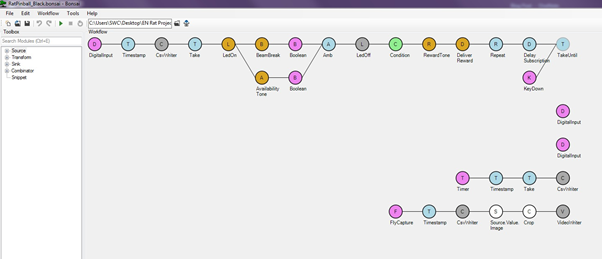

The automated aspect was provided by a "poke" provided to us out of time convenience. The basic principle is relatively simple, above the poke is a piezo buzzer that sends an audible tone to indicate when a reward is available (equivalent to the sound of the clicker). Within the protruding part of the poke is an infra-red transmitter and receiver, once the beam is broken simultaneously a liquid reward of strawberry flavoured Ribena is dispensed (at a small enough volume to not drop) and the tone is stopped. This procedure was programmed into the attached Arduino board with the visual programming language Bonsai running on a PC.

In addition, two tubes (enclosed in a glove) were fitted with a set of infrared transmitters and receivers wired up to an additional Arduino and the same Bonsai code. Once either of these beams were broken the code was programmed to activate the tone and reward protocol of the poke as outlined above.

Finally, to create an environment where the rat would hopefully be more comfortable and explorative, we conducted all habituation and experiments in darkness. In order to gather recordings infra-red (IR) LEDs were placed above the set-up and a camera with an IR filter was mounted above to both record and to give real-time footage to observers. To compliment the recordings the Bonsai code included instructions to export a time-stamp of successful events (e.g rewards, balls dropped into tubes). Both the video files and time-stamp data was then processed in Matlab.

Methods

The first stage, two 30 minute sessions over two days, involved habituating the rat to the arena and allowing it to feel comfortable secure when inside the set-up. Following this the rat was trained to associate the beeping tone with a Ribena reward. This was conducted by writing in the Bonsai code for the buzzer to beep at a random exponential interview set at a maximum of 50 seconds. Once the rat had learnt this association the plan was then to introduce up to eight marbles in strategic locations near to the holes. At this stage of the experiment the code was set-up to only initiate a reward tone once the infra-red sensors in the tubes were activated. Following a successful learning of this paradigm the aim was then to introduce the additional room into the set-up and see if the rat could apply what he had learnt throughout training to this new altered environment.

Results

Initial stage training (days 1-2): The rat was very quick to learn the association between the tone and a reward over four sessions 30 minutes in length. The video file below shows the first five minutes of one of these initial training sessions. From the corresponding heatmap it's easy to observe that initially the rat was more interested in spending time in two corners rather than near the poke (located in the bottom, middle of the heatmap). However, when compared to the overall heatmap for the 30 minute session it's clear to see that as the session progressed the rat was choosing to spend a greater proportion of it's time nearer the poke, either due to collecting a reward or in anticipation of the the tone and reward.

Late stage (days 2-10): Moving onto the next stage of the plan as outlined in methods we accounted issues with our methodology with twice daily training sessions varying in length from 30 to 40 minutes. During this stage we were reminded of the lesson learnt in our short trial as lab animals. Although the rat was able to knock in a few marbles accidentally the rewards were too few and far between to create any lasting association. As a result he failed to quickly learn any association and became bored and disinterested in the marbles in general. Final stage (days 10-13): In attempt to create a stronger interest in the marbles we adapted our Bonsai code with a "key down" command to manually initiate the reward tone upon interaction with any marbles. Although this did yield an increased level of interaction after a few training sessions, restrictions of time stopped this fully developing into the desired behaviour.

Conclusion

We set out to probe the intricacies of animal behaviour training and to learn whether in two weeks a rat could learn a simple behaviour task and apply the logic it learnt to an adapted environment. Due to a combination of time restraints and oversimplified experimental design we were unable to reach the final stage of the experiment and expose the rat to an adapted environment. Despite this the experimental experience raised a variety of interesting questions of what the best training strategy could be for the kind of task and how it could be optimised. For example had we created a more sophisticated system for associating marble interaction with reward (possibly via an automated response coded into Bonsai) we may have seen faster progress through the training schedule. In conclusion, we believe that with adequate adaptations that this training paradigm with a similar set-up could yield an effective approach for studying this and a variety of rodent behaviours.